Here’s what they’re saying about Julia Keefe:

This is a story about a little girl – now a young woman – who dreamed big and is living her dream. Her name is Julia Allane Keefe, and she is a Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) tribal member. Her father, Tom Keefe, is of Irish descent and is best known as one of the top treaty lawyers of the Boldt Era. Her mom is JoAnn Kauffman, founder and president of Kauffman & Associates, a Native American consulting firm. Many at Muckleshoot know her auntie, Senator Claudia Kauffman.

This is a story with a message, and its message is to young girls: Dream big, work hard, and do it all with love in your heart. You can achieve anything you set your mind to. We’ll let Julia take over her story from here...

* * * * *

I remember sitting crossed legged on the floor, listening to my kindergarten teacher as she read us a story. We had moved to Kamiah, ID, a small lumber community on the Nez Perce Indian Reservation, only a few months before. I was surrounded by friends and cousins. I remember I was wearing a dress with flowers and white tights, which was odd for me given my tom-boy tendencies. I had a melody bumbling around in my tiny human brain. I was chasing it, following it as it rose as fell, like I was following a butterfly through my mind.

“Julia, is that you humming?” my teacher asked me.

“You can hear that?” I replied in total disbelief.

The whole class erupted in laughter. My teacher put the book in her lap and chuckled. “Of course, we can hear that!”

I don’t recall being embarrassed at all. I just remember being completely shocked. I had just discovered something about myself. The melodies in my head can come out, people can hear them. I can make musical sounds all on my own.

It is a funny memory now, in my mid-thirties, sitting in a hotel room in southern California. I am working with California State University Long Beach for the week, performing in outreach engagements to elementary school students and teaching them about the history of jazz. All the students will get to join us at the performing arts center on the university campus for a private performance on Friday morning. It is an honor to take part in their musical development in this small way.

Oh, that I could go back to kindergarten Julia and tell her where those melodies in her head would lead her. I tear up at the thought.

My journey with jazz has many a twist and turn. My first musical memory was listening to the sounds of Billie Holiday as my mother was cleaning in the living room. I remember the orchestra as it began to play and the muted trumpets creeping over the strings like fog. Billie’s voice came in as the ensemble fell in a decrescendo: “You ain’t gonna bother me no more…”

Billie was the voice that haunted my childhood in the best possible way. Even as my interests wandered to and fro, to basketball and baseball, and even during that time I was absolutely convinced I would grow up to be a detective in the NYPD, Billie’s somber and evocative sounds would somehow appear in my mind: Got only one heart, one heart with no spares. Must save it for lovin’ somebody who cares…

“It was such a fun gig... I was nervous and intimidated by the room. But as more people filled up the space, more smiling, loving faces settled into their tables, I remembered who I am, where I come from, the work I have done, and that it is such a gift to make noises for a living. And when I got on stage, I was home.”

– Julia Keefe, after performing at Manhattan's legendary Birdland jazz club.

It wasn’t until my first singing engagement that music really took hold as something I could practice and actively participate in. It was Martin Luther King Day and the parade in Kamiah needed someone to sing the national anthem. A friend and I ended up in front of the microphone, and after uttering a few of the words, I forgot the melody and ran off stage crying.

Not the greatest career-launching moment, but the elders in my tribe, my grandmas who raised me and baptized me in my church, they saw something – or heard something – that needed more attention. They advocated for me to sing the national anthem at the biggest basketball game of the season: Kamiah Kubs vs the Lapwai Wildcats. Everyone in both towns would be in the Kamiah High School gym for the game.

It was a daunting task. But I remember as soon as it was made official, I began practicing. I worked with the elementary school music teacher. I learned what I could of the song on my recorder. I practiced that melody hard.

I should also mention I had a speech impediment at the time as well. There are so many R’s and L’s in the Star Spangled Banner, and yet I was not deterred. The day came and I donned my little red velvet dress and black little shoes. I sat next to my mother right next to the announcer’s desk on the gym floor as giant high schoolers pounded basketballs up and down the court in their warmups. I was trying to play it cool, singing along with the pep band and cheerleaders, but inside I was nervous beyond belief. When the moment came, and they announced my name, I stood up, took the microphone, and took a breath...

That little 8-year-old child did such a great job. She sang every note, the pitch never wavered, and her speech impediment was charming. She remembered all the words. She hit that last high note on “free” – or rather “fwee” – and she closed the song strong. Of course, as soon as she finished, her shoulders slumped over in shame, handed the announcer the microphone, and shook his hand with her head hung low. Oh, little Julia, you did so well, and you have no idea how proud you will become of this performance. And your speech impediment will sort itself out next year, kid, no worries...

Did I plan on becoming a singer? I would argue no, that it was more of an accident. But those who knew me then say I always was singing. So perhaps it was some sort of divine calling, or something that was in me from the very start. I was just given the opportunity and the encouragement from my grandmas to pursue it beyond the melodies in my head.

After we left Kamiah, we moved to Spokane, WA. There I was able to study music in the school choir. It was in this setting that I was also exposed to jazz beyond the albums and recordings of Billie Holiday. Jazz music was the central focal point of our musical education, as was competing at the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival each year. As a seventh grader, newly introduced to the blues and how to improvise, my teacher said, “Okay, Julia, you’re going to take the solo.”

“I’m sorry, what?”

“You’re going scat sing over this part of the song,” he said with a certain level of finality. I felt completely unprepared for the task. My thoughts were racing with messages of doubt, shame, and resentment. How could I “scat” over this song? How could I “take a solo?” After I ranted and raved at the dinner table, my father said, “Just do it, Julia!”

And the next day in class, I just did it. Fortunately, I didn’t crash and burn as I had thought I would. From there, we went on to Lionel Hampton to compete. I enjoyed soloing so much, I was thrilled to find out that Lionel Hampton had a solo vocalist competition. I was determined to compete the following year.

I competed in the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival as a solo vocalist every year, constantly learning and adapting to the competition. It felt like a game of chess that I was playing against myself. I would read the adjudicators comments, listen to the recordings of my performances, and I made special effort to see the other soloists in my division. The winners were always easy to spot, and I used my time after Lionel to study their performances as well and analyze what is was exactly that set them apart.

Eventually, my time came. My senior year of high school, I won my division and got to perform on the main stage at Lionel Hampton. Ten years later, I would be back on that stage as a guest artist performing with the Lionel Hampton Big Band and opening for Esperanza Spalding.

During high school, while marinating in my jazz nerd-dom and reading up on Bing Crosby, I happened upon the name Mildred Bailey. Bing, who also attended my high school alma mater of Gonzaga Preparatory School, credited Mildred as being a huge influence on him early in life. I thought it so strange I had never heard of her before. I did a little more research and came to find out that not only was she the first woman to sing in front of a big band in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but she was also a Native American woman who spent her formative years in Spokane. What are the odds?!

As I am prone to do, I became obsessed with finding out more about this influential yet largely forgotten jazz figure. Funnily enough, I found the Billie Holiday album I had once listened to as a child and in the accompanying booklet, there was a graphic of the Billboard’s top vocalist and Billie Holiday was place third behind Ella Fitzgerald at number two and Mildred Bailey in the top seat. Our paths had crossed before and I had no idea.

I visited the Jazz Hall of Fame at Lincoln Center in New York City during that time and found that only a handful of women were included in those hallowed halls, and Mildred Bailey was not one of them. Recognizing this as a profound oversight and injustice, I made it my mission to have her inducted and her picture to be hung upon the wall as an important and influential figurehead in the evolution in jazz.

In 2009, I premiered my Mildred Bailey tribute show titled “Thoroughly Modern: Mildred Bailey Songs” at the National Museum of the American Indian for Jazz Appreciation Month. I was later invited to perform for the State Department in honor of Mildred Bailey and her contributions, as well as the opening of NMAI in New York with their exhibit “Up Where We Belong.” Mildred has yet to be inducted at the Jazz Hall of Fame at Lincoln Center, but her recognition continues to rise. I am so proud of the part that I have played in honoring her legacy.

I am still in the midst of my Mildred Bailey crusade. It has taken on many iterations and I always dedicate a song to her on every show. Nowadays, I am focused on my Indigenous Big Band, an effort I created with my dear friend Delbert Anderson (Dine). We aim to highlight the diversity and vitality of Indigenous people in jazz: past, present, and future.

The band is part of a much larger legacy of Indian boarding school survivors returning home to their tribal lands and creating marching bands, big bands, and small jazz ensembles throughout Indian Country. Not only do we feature the work of Mildred Bailey, we uplift the legacy of Jim Pepper (Kaw) and contemporary artists like Delbert and Mali Obomsawin (Abanaki of Odanak).

We recently had the great honor of performing on the same stages as many jazz greats at Birdland and Joe’s Pub in New York City, and we’ll be at Washington, DC’s Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in May, headlining the Mary Lou Williams Jazz Festival with Esperanza Spalding as a guest artist.

Julia Keefe (Nez Perce) is an internationally acclaimed Native American jazz vocalist, bandleader, actor, and educator currently based in New York City. Her professional career has spanned nearly two decades, and she has headlined marquee events at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C., NMAI-NY, as well as opened for the likes of 20-time GRAMMY Award winner Tony Bennett and 4-time GRAMMY Award winner Esperanza Spalding.

Her life’s work is the revival and honoring of the legendary Coeur d’Alene jazz musician Mildred Bailey and is leading the campaign for Bailey’s induction into the Jazz Hall of Fame at Lincoln Center. In addition to rehearsing for an upcoming album, she is currently directing the Julia Keefe Indigenous Big Band, a new project highlighting the history and future of Indigenous people in jazz. The Mildred Bailey Project released its first studio recording in January 2024 and has signed on with a national management firm based in Los Angeles.

The last few Fridays of the season brought Muckleshoot employees out dressed in their best Seahawks gear for a group photo to show that the 12’s spirit runs deep.

The two core components of the 7th annual Salmon Jam tournament are teaching kids the dangers of smoking cigarettes and vaping, and empathy for others.

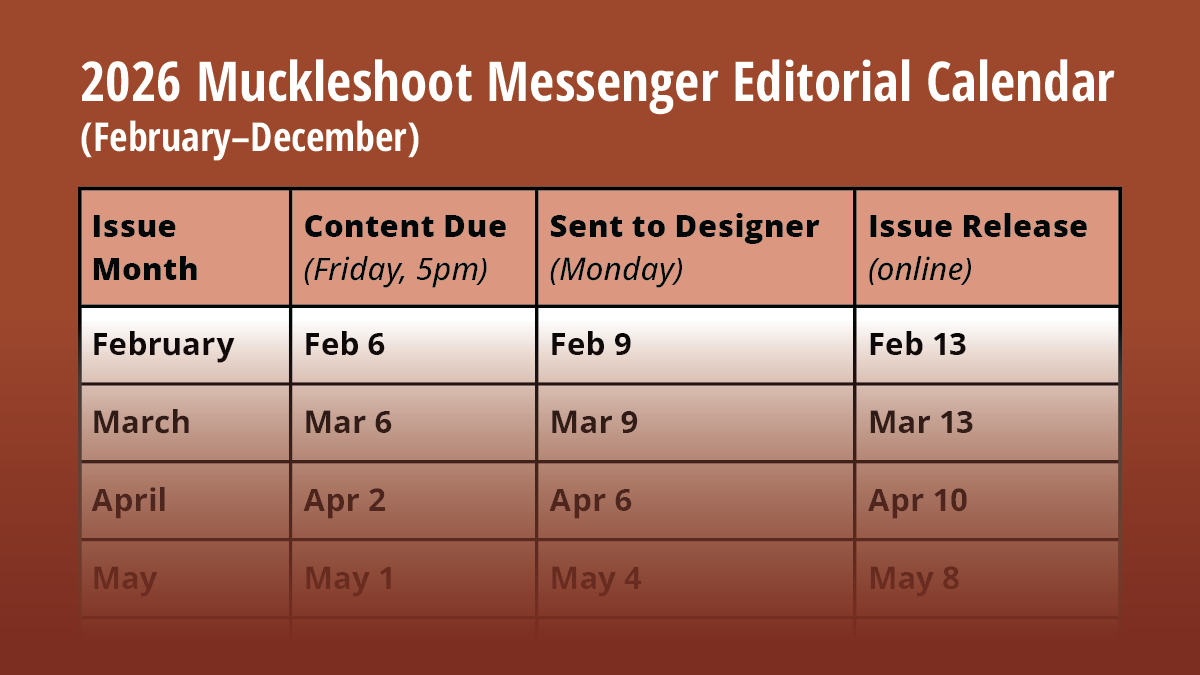

We love hearing from our community. To help us share stories in a timely and organized way, all content for the Muckleshoot Messenger is due by 5pm on the first Friday of each month.

Elders from the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe and their loved ones gathered together on Jan 16 at the Elders complex to celebrate the New Year. The gathering was a joyful and welcoming community celebration.

The Muckleshoot Messenger is a monthly Tribal publication. Tribal community members and Tribal employees are welcome to submit items to the newspaper such as announcements, birth news, birthday shoutouts, community highlights, and more. We want to hear from you!